Cardiomyopathy Syndrome (CMS)

Cardiomyopathy Syndrome (CMS) is a serious heart disease affecting farmed Atlantic salmon in seawater.

The disease was first reported in 1985. It is now present in all Norwegian production areas, where it poses significant challenges to both fish health and welfare.

CMS is one of the major causes of mortality in Norwegian salmon farming, with a high number of reported detections each year. The economic impact can be severe, as the disease typically affects large, harvest-ready fish. In recent years, newly sea-transferred smolt have also been affected. Research indicates that piscine myocarditis Virus (PMCV), the cause of CMS, is highly prevalent.

Mortality associated with CMS outbreaks may be slightly or moderately elevated over an extended period or present as sudden, high mortality events often triggered by stress.

Pathogen and Transmission

In 2007, CMS was shown to be transmissible via intraperitoneal injection of heart and kidney tissue homogenate from infected fish to healthy fish, thus strengthening the hypothesis that the disease had a viral etiology. In 2009, a cohabitation trial confirmed waterborne transmission. In 2010, researchers from the Norwegian School of Veterinary Science and the Norwegian Veterinary Institute identified a novel virus—piscine myocarditis virus (PMCV)—as the causative agent of CMS.

PMCV belongs to the Totiviridae group. It is a non-enveloped, double-stranded RNA virus with a relatively small, unsegmented genome that likely codes for only 3–4 proteins.

All Norwegian PMCV isolates examined from salmon are genetically very similar and appear to belong to a single genogroup.

The only known reservoir for PMCV is farmed salmon. Studies of wild salmon, marine wild fish, and environmental samples provide no evidence that these serve as significant hidden reservoirs.

PMCV has been detected in about 0.25 % of spawning wild salmon, and CMS-like lesions have occasionally been reported in wild fish. PMCV has also been identified (Ct value of 15) in an escaped farmed salmon in Numedalslågen. In a large study of 32 marine wild fish species, PMCV was found in silver smelt (Argentina silus) using PCR. However, the strain in smelt differs from that in salmon, suggesting limited potential for interspecies transmission. Other salmonids, such as rainbow trout, appear resistant to PMCV.

Some farm sites are more frequently affected than others, possibly indicating unknown reservoirs or contributing environmental or operational factors.

CMS has not been detected in hatcheries. Although PMCV RNA has been found in low levels in freshwater-phase fish, there is no evidence for vertical (parent-to-offspring) transmission. A long period may elapse between initial PMCV detection and the onset of disease and mortality. In some cases, the virus is detected early in the seawater phase without necessarily leading to clinical disease.

How the virus is introduced and spreads between fish in field conditions remains unclear. A research study completed in 2019 detected PMCV in all 12 surveyed salmon farms along the Norwegian coast (from Agder to Finnmark), and in all monitored cages (2 per site), indicating the potential for effective transmission between cages.

Like other non-enveloped viruses such as IPNV and nodavirus, PMCV is likely more resistant to environmental stressors like temperature, low pH, disinfectants, and drying than enveloped viruses. However, because PMCV cannot be cultured in vitro, specific data on its resistance is lacking.

Further research is needed on PMCV and CMS, especially concerning virus shedding, transmission, environmental persistence, disease progression, and other contributing risk factors.

Clinical Signs

There appears to be a clear relationship between viral load and disease severity. Using specific viral staining (in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry), PMCV is consistently found in areas with typical heart pathology. Virus is usually detected in association with CMS outbreaks or in fish showing characteristic heart lesions. PCR testing may in some cases detect PMCV in salmon shortly after transfer to seawater, and the virus can persist for an extended period before disease develops.

While daily mortality in CMS-affected farms is usually low, prolonged outbreaks can lead to significant cumulative losses—especially in large fish. In recent years, cases of early-onset CMS have been reported, affecting fish as small as 100–300 g. CMS has not been observed in hatcheries.

The incubation period in the field is unknown, but experimental infections show the first histological signs appearing about six weeks post-infection. The disease progresses slowly, consistent with a chronic condition. Fish may die suddenly without showing external clinical signs.

There are typically few moribund fish (in CMS-affected pens. However, fish may exhibit signs of severe circulatory failure visible both macroscopically and microscopically. Some dead fish with severe heart lesions may appear outwardly normal, but typical gross changes can include exophthalmos (bulging eyes), scale pocket edema, and petechial bleeding on the abdomen. On necropsy, signs of circulatory failure may include ascites, dark liver, fibrin coatings on the liver, and/or fluid in the body cavity. In advanced cases, cardiac tamponade (fluid accumulation around the heart) can impair heart function. Eventually, the atrial wall may rupture, causing cardiac arrest.

Diagnosis

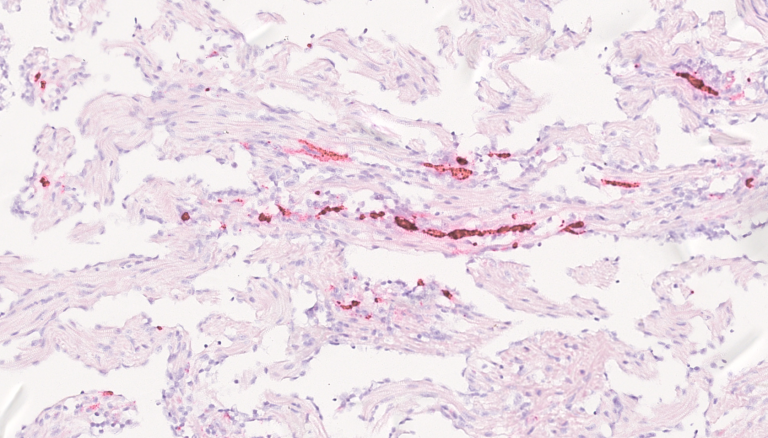

Currently, CMS is diagnosed histopathologically, based on typical clinical history and heart lesions only. Characteristic inflammatory changes are observed primarily in the inner, spongy layer of the atrium and ventricle. The compact myocardium is usually unaffected, but in severe cases, inflammation may also appear near coronary artery branches. In advanced cases, epicarditis with high cellular density can occur. Secondary changes in the liver and spleen—likely due to circulatory failure—may also be seen. Real-time RT-PCR for PMCV is commonly used for surveillance in asymptomatic groups. PCR is also useful in distinguishing CMS from similar conditions, especially in mixed infections or early stages. New in situ hybridization techniques show promise for differentiating various forms of heart inflammation but are not yet used routinely.

Differential Diagnoses

The main differential diagnoses for CMS are:

- Pancreas disease (PD)

- Infectious salmon anemia (ISA)

- Heart and skeletal muscle inflammation (HSMI)

PD and HSMI involve the exocrine pancreas or skeletal muscle, thus differentiating these conditions from CMS.

Prevalence

CMS was first described in Norwegian farmed salmon in the mid-1980s. Although most detections have historically originated from Møre og Romsdal and Trøndelag, the disease has now been confirmed at aquaculture sites across the Norwegian coast.

The field study previously mentioned suggests that PMCV is widespread in Norwegian salmon farms along the whole coast.

Similar disease patterns have been observed in Scotland, Canada, and the Faroe Islands. In recent years, an increasing number of CMS cases have been reported in Ireland and Scotland, where the disease has become a major challenge both economically and for animal welfare in the aquaculture industry.

Risk Factors for CMS Outbreaks

CMS does not follow a strong seasonal pattern. The risk of outbreaks increases the longer fish are in seawater. Spring stocking carries a lower risk of developing CMS than fish stocked in the autumn, but there is also variation between different groups of spring-stocked fish: In some areas, fish stocked late in the spring have the lowest risk, while in other areas, those stocked early fare better.

Evidence suggests a connection between CMS outbreaks and hatchery phase conditions. Field reports show variation in which groups become diseased during an outbreak at a single site, often fish from the same hatcheries develop disease year after year.

CMS-related heart damage makes fish more vulnerable to stress and physical challenges. Handling events such as grading, transport, delousing, and medication can increase mortality during outbreaks. Other possible contributing factors include rapid growth, environmental conditions, nutrition, and insufficient exercise. Once CMS is diagnosed at a site, all stressful handling should be minimized until the fish can be harvested, to reduce mortality.

Control Measures

CMS is not a notifiable disease, neither in Norway nor in the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) guidelines. Therefore, there is no official eradication program.

There is currently no vaccine against CMS, but vaccine development is ongoing. Breeding companies offer QTL-selected strains with increased resistance to the disease. Special “functional feeds” are also available to reduce heart damage and mortality during outbreaks.

%20(1).jpg)